Introduction

I ran an experiment to understand how well ChatGPT 3.5 analyzes qualitative data from an anthropological perspective, an approach used when companies need to generate new innovation. If done well--not just creating a summary or completing a word count but using anthropological theory as a lens through which data is interpreted--ChatGPT could speed up the very time-consuming process of unlocking deep human insights from qualitative data sets.

So, how did ChatGPT perform when it attempted to use various anthropological theories in analyzing the same data set? ChatGPT uncovered some thought-provoking concepts in its analyses, but did not consistently yield high-quality, theoretically-sound responses. ChatGPT is not good enough (yet?) to analyze and interpret data in a way that leads to valid, compelling human insights which can lead to breakthrough product innovation.

The Details

I ran an experiment to understand how well ChatGPT 3.5 analyzes qualitative data from different anthropological theory perspectives, including structure-functionalist, symbolic, postmodern and decolonial theories. I asked it to analyze a 3,471 word-portion of this interview transcript (see Appendix A: Transcript Portion Used for Analysis, from Family Life and Work Experience Before 1918, 1870-1973, data collection from the University of Essex Department of Sociology). For each analysis, I prompted ChatGPT with the following phrase: ‘Analyze this data from an anthropological structure-functionalist perspective:’, and then pasted in the textual data set cited in Appendix A. I used the same prompt three more times, substituting the names of different anthropological theories (structure-functionalist; symbolic; postmodern; decolonial) each time, and then pasted in the portion of the interview transcript after the prompt (see Appendix B: Experiment Prompts and ChatGPT 3.5 Responses).

Chat GPT 3.5 performed the best when I asked it to analyze the data from a symbolic anthropological perspective: it gave richer, more nuanced responses that connected concrete behavioral data points in the data set to abstract cultural concepts more frequently than the structure-functionalist, postmodern and decolonial perspectives. When trying to brainstorm new product opportunities or innovations, having concrete findings paired with abstract cultural concepts can be more powerful than having concrete findings alone. Abstract cultural concepts framed in a high-level way help those who are brainstorming think about human motivations, mental models, and how people see the world around them, which serves as fertile ground for thinking of new product or service ideas, while concrete findings ensure brainstormers stay grounded in human needs and behaviors.

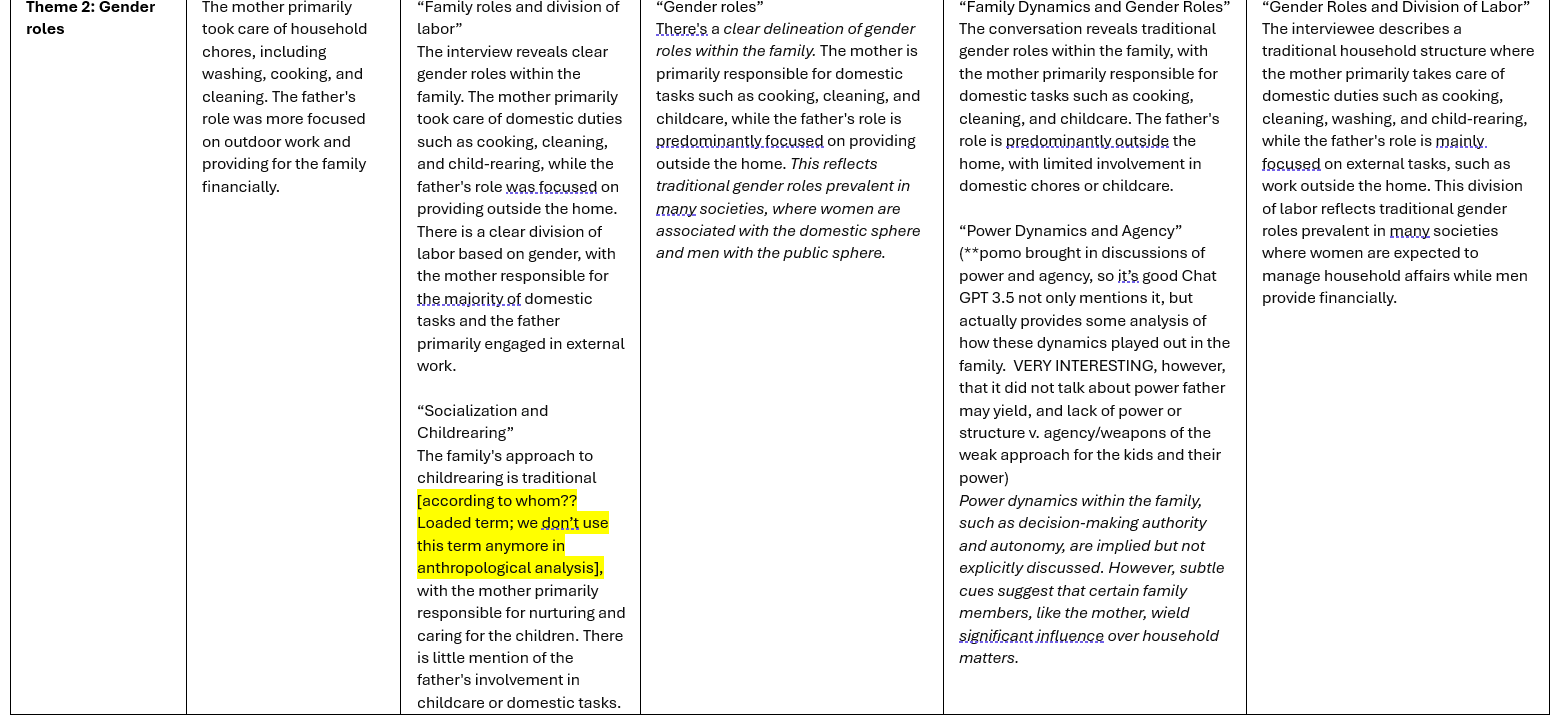

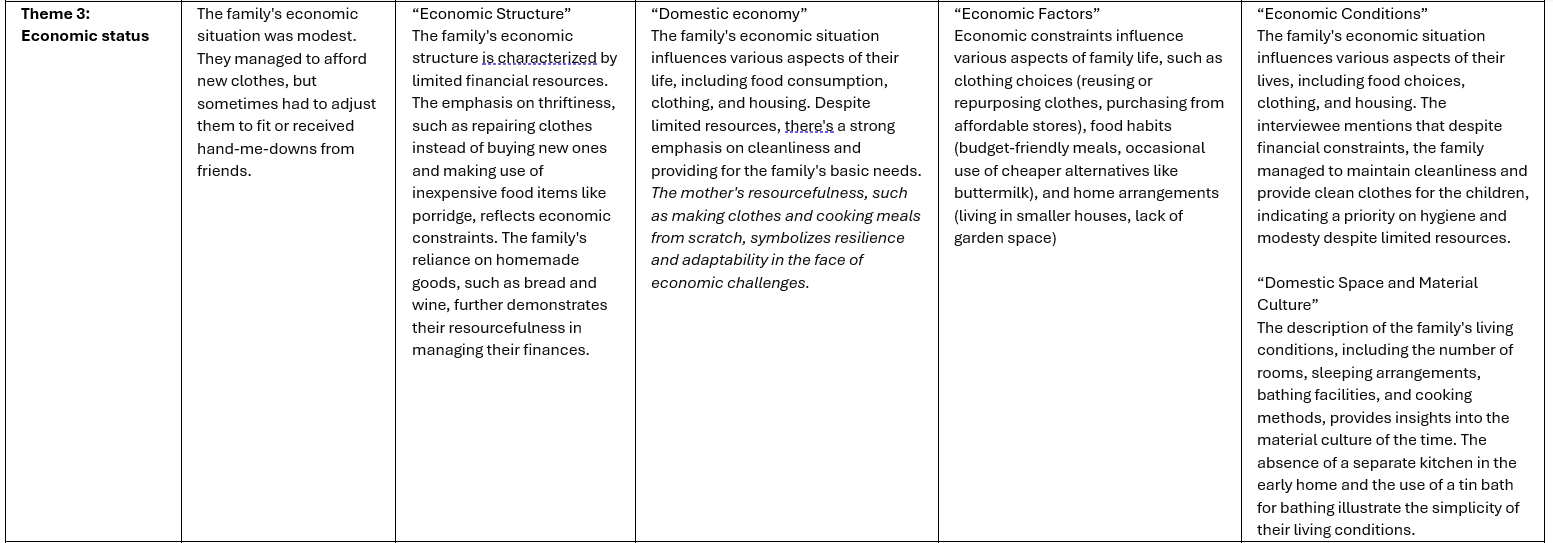

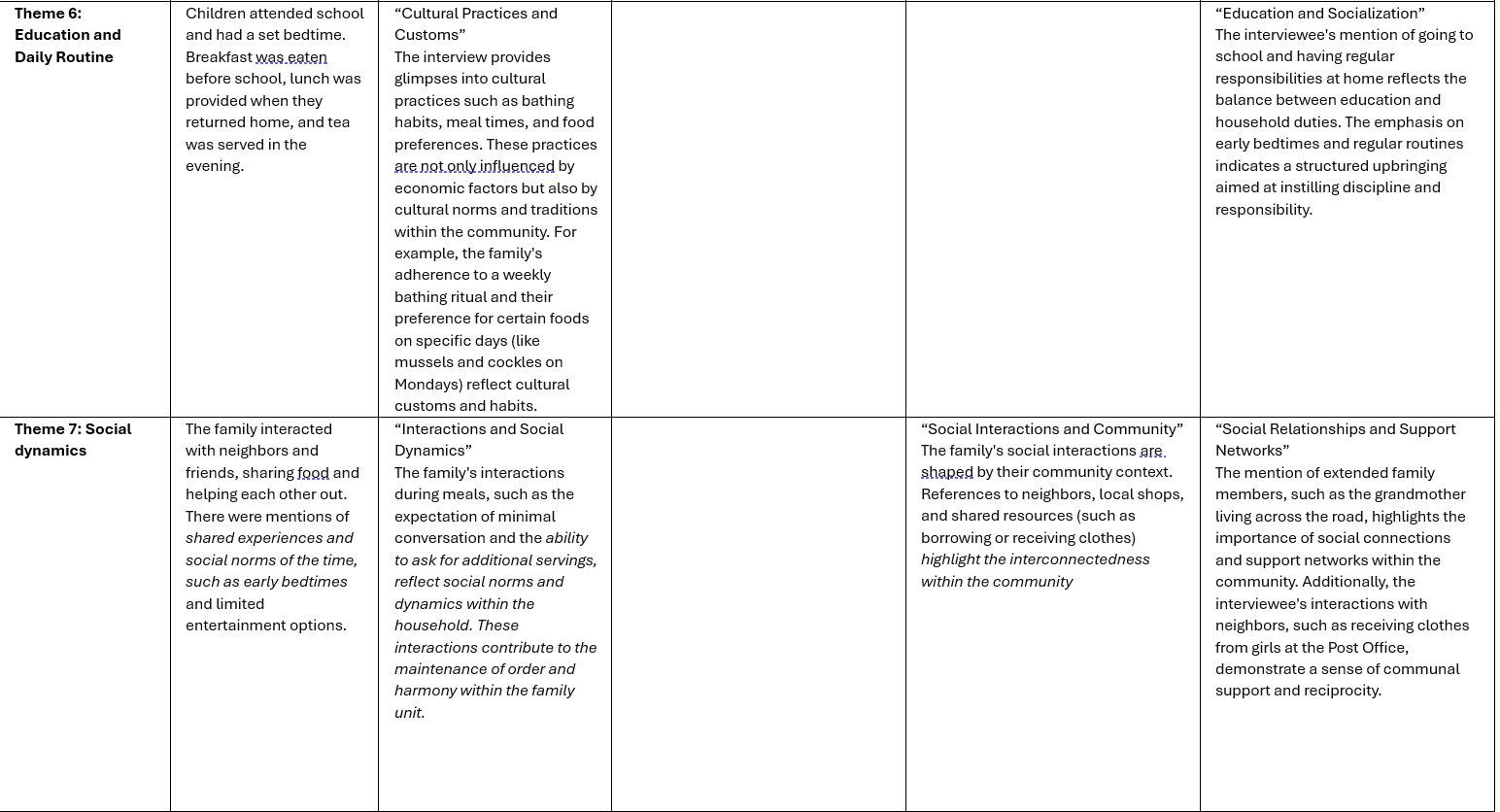

An example of this is ChatGPT’s analysis of ‘Gender Roles’ in the data set (see Appendix C: Table of ChatGPT’s Responses Organized by Theme and Theory). The symbolic anthropological perspective on gender roles included discussion of abstract cultural concepts like ‘domestic sphere’ and ‘public sphere’, whereas the other anthropological perspectives tied the concrete data about the mother’s tasks in the home and the father’s tasks outside of the home to more concrete ideas like physical space. For example, ChatGPT’s structure-functionalist anthropological analysis yielded insights about ‘domestic tasks’ for the mother v. ‘external work’ for the father referenced in the data set; ChatGPT’s postmodern analysis highlighted the mother’s role as focused on ‘domestic tasks’ while the father’s role focused more ‘predominantly outside the home’.

In addition, ChatGPT responded with the same concepts in its analysis (‘domestic tasks’ appears in both structure-functionalist and postmodern analysis; more examples are in Appendix C, below) when it was asked to use different anthropological theories as framing mechanisms for analysis. This makes clear that ChatGPT understands the different definitions of anthropological theories, but its lack of analytic depth and nuance shows it does not know how to apply anthropological theory consistently and rigorously to elicit deep cultural understanding.

Another example of ChatGPT’s lack of depth and nuance emerged when I asked it to analyze the data from a decolonial perspective. Instead of analyzing the data from this perspective it responded by defining anthropological decolonial theory. In its final summary from its decolonial analysis, ChatGPT noted its analysis, “highlights the importance of adopting a decolonial lens to critically examine power dynamics, inequalities, and colonial legacies embedded within everyday practices and structures.” In fact, ChatGPT did not do this in the analytic categories it created for its decolonial analysis, nor in the supporting data points in each category. The supporting data points hinted at power structures and inequalities but did not explicitly indicate where the data elucidated a power relationship or inequality.

Conclusion

The inconsistency in its analytic responses and lack of depth and nuance mean that for now, ChatGPT 3.5 is not ready for use as a reliable substitute for human anthropological analysis meant to generate human insights for new product or service innovation in industry.

APPENDIX A: Transcript Portion Used for Analysis, from Family Life and Work Experience Before 1918, 1870-1973, data collection from the University of Essex Department of Sociology

You and your two brothers - you were all born then?

R:

Yes. Yes. Yes. Because - we moved from there into Lee Gate Lane in the double house you see when our Tom went working full time. Because the house rent was only three and nine.

I:

This was the first house in Lee Gate Lane?

R:

No, the second one. Two up two down.

I:

The first house, one up and one down you'd be a bit crowded wouldn't you? Was there anybody else at all besides your parents you're your brothers and yourself living there - you didn't have -?

R:

No. And me grandmother lived across road.

I:

Did your mother have anybody to help her in the house?

R:

No. Never. Not 'til I grew up you know.

I:

Was the washing done at home?

R:

Yes.

I:

Did your mother or father mend or make any of the family's clothes?

R:

Oh, me mam used to make our - mine like.

I:

But not the boys?

R:

No. No.

I:

Did she mend?

R:

Oh yes. She had to do. 'Cos we didn't get a big wage.

I:

The clothes that were bought - were they new?

R:

Oh yes.

I:

They were always new?

R:

Mm. More or less.

I:

Were they sometimes not?

R:

Well, I remember having one or two things cut down and made to fit me. Because I used to be friendly with them at the Post Office, now they had girls and they worked at - well, as they grew older Fanny worked at - Post Office in town - general - and they used to give me clothes and I had them cut down and made to fit, you know.

I:

The clothes that were bought.....

R:

They were always new.

I:

Were they bought in town or where?

R:

Yes. Yes. They were bought in town.

I:

Any particular shop?

R:

No. No. She used to go just anywhere - where she wanted to go.

I:

What about shoes?

R:

Oh well, I used to go - I remember going to Morris's in Market Street at one time. I don't know whether there's anybody living along of them now. I don't know whether it's not Tylers now.

I:

Did all the family get their shoes from there?

R:

Yes, I think they did.

I:

Did your father ever mend your shoes?

R:

No, I don't think so. I think we used to take them to Jack Bridges at Bradshaw Chapel. That's - yes. That is - where you turn round it was - a shoe shop and he used to mend clogs and all.

I:

Did your father help your mother with any of the jobs in the house?

R:

No, not really. Because he was always doing some jobs outside.

I:

Did he ever do anything like cleaning or cooking or washing up?

R:

No.

I:

Would he make the fires?

R:

Oh he may do that because, you know, at that time - they used to rake in winter times, you know, and all that fires -

I:

Keep it in all the time?

R:

Yes, yes.

I:

Did your father do any of the decorating or repairs or improvements or anything to the house?

R:

No. No. All - it belonged to the crofters - the croft used to do it all.

R:

Did he do anything for you as children like dressing or undressing or bathing you. Not as I remember.

I:

Did he ever read to you or tell you stories?

R:

No. No, he wasn't a reader, me dad, but he had a good memory.

I:

Did he take you out without your mother?

R:

No.

I:

Or look after you when she went out?

R:

Well, she never went out a great lot not them days they didn't. No.

I:

Did you yourself have any tasks to carry out regularly at home to help your mother?

R:

Oh yes, I used to wait for washing and ironing and take them back to ladies where they had to go.

I:

Did you do any other jobs besides that?

R:

Well I used to do mopping and all that you know.

I:

Was this your regular responsibility?

R:

Mm. And I used to go out shopping.

I:

How long did you go on doing these things - 'til after you left school? or 'til you got married?

R:

Well my - me mother were dead when I got married. I was about twenty-nine when I got married. And did most of work you know like when I were working.

I:

So you went on doing a lot of housework after you started work?

R:

Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. And I looked after them after me mum died you know.

I:

Did your brothers have any jobs to do when they were children?

R:

They used - our Fred used to come with me - errands you know and that. No, they used to go fishing.

I:

Did the older children have to help the younger ones?

R:

No.

I:

With anything like dressing or feeding?

R:

No, no. Me mam used to look after us. She were a good mother.

I:

Did the younger children help the older ones at all?

R:

No.

I:

Were you expected to go to bed at a certain time?

R:

Oh yes, we were - yes - we were always in bed early. Well, I've gone to bed at half past eight when I were working. Because there wasn't a lot, you know, going on them days. Not in the country, you know, you had to go to town.

I:

When you were going to school what time did you have to go to bed?

R:

Oh, want to bed early. Used to be all in bed by ten - when we were working. We were never out of bed any of us late.

I:

What time did you go to bed as children?

R:

Oh we had to go to bed early - me mam made us, you know, about eight o'clock. Yes.

I:

Did your mother or anybody else put you to bed?

R:

No.

I:

Not even when you were very small?

R:

No. Only me mother. Me mother looked after us.

I:

How old would you be when you started to put yourself to bed?

R:

I couldn't say. 'Cos we used to go if we were tired, you know, we'd go upstairs and we didn't bother.

I:

How old would you be when you started doing that?

R:

Eeh, I don't think I know. I can't go back, you know. Can't go back -

I:

Did you share the bedroom or the bed with anybody?

R:

No. No, I had a bed of me own.

I:

What about the bedroom - would there be other beds in the bedroom?

R:

No. The boys slept in the other room with me father and mother and I had the other room.

I:

What about when you were in the house with only one room upstairs?

R:

Well they had - we were all small then, you know, and we all slept - yes.

I:

How many beds would there be there?

R:

Oh there were one - single bed you know and like a - a bigger one for the boys and then there were me mothers and fathers. Yes.

I:

So there were three beds in that one room?

R:

Yes, yes. 'Course they used to - they used to say, now whether it were correct, but one time they used to have round beds, you know, when they had these big families. 'Course we'd only three of us. But they said they used to have these single beds - you know, single houses and they used to all have a - a round bed they used to say.

I:

Have you any reason to suppose that this was true?

R:

Well I don't really know - I don't. Because, you know, they did have big families. Yes. But I never saw any. But I have heard 'em say some slept at feet, you know, I could take that in.

I:

Which room did you bath in?

R:

Well, me mother used to have a big tin bath, you know, great big one and we used to have it at front of fire.

I:

You'd only one room downstairs hadn't you?

R:

Yes, that were all, yes.

I:

How often did the various members of the family bath?

R:

Well, we always had a - a bath like at Friday night. Every week. Yes, Every week. And then we used to have good washes, you know.

I:

But was it just the one night the bath was got out?

R:

Yes, as we had the bath, yes, yes.

I:

When did you have clean clothes to put on?

R:

Oh well, me mother used to keep us clean, she used to wash practically every day you know. She were very particular over clothes - very. Like she said, we weren't well off but we had clean clothes.

I:

Where did you have your meals?

R:

In the living room. Yes. Oh there were no kitchens like they do now you know.

I:

No, you'd just this one room.

R:

Yes. 'Course we - we did have a work in the back kitchen and we used to have our food in the living room.

I:

This was when you'd moved into the other house?

R:

Yes.

I:

But when you were in the one with only one room?

R:

Oh yes, we had to do - yes, yes, yes.

I:

Where did your mother cook - obviously it would be in the one room?

R:

Yes. Well, they used to cook a lot on the fire, you know, because they had a oven attached to the - fireplace you know. And they used to put it down and they cooked with a big pan to make broth, you know. And then cooked their bread and all that in the oven. They made all their own bread.

I:

When you had the two rooms was the coal fire and the oven in the living room or the kitchen?

R:

Yes. No, in the living room.

I:

Did your mother have any other cooking equipment like a gas stove of any kind or a gas range?

R:

No, I don't think we had any then. No.

I:

When you were a child what time was breakfast eaten?

R:

Well we had to go to school you know for nine so it were between eight and nine.

I:

Which members of the family would be present then?

R:

Well we were all three - Tom, Fred and me. And me mother. And me dad went out, you know, early.

I:

How did he manage for his breakfast - did he get it himself?

R:

No, me mother used to put it up and they used to have it you know when they were outside working.

I:

He didn't have a meal before he went out then?

R:

Well he had a drink and something to eat you know and then he'd take his breakfast with him. And his dinner he'd get if she - me mother hadn't made him one to take. 'Course working outside it were hard work to warm 'em you know what I mean.

I:

What did you usually have to eat and drink for your breakfast?

R:

Well, it just depended what me mother had. But at one time you know it'd be a lot of porridge we used to get and we'd have eggs - 'cos eggs used to be cheap then, and bananas you know. 'Cos you could get them very cheap. And they they'd buy bacon - and eggs.

I:

Did you have anything special on Sundays for instance or did you still have your porridge?

R:

Oh no, we used to have - bacon and egg and we used to have meat and all like that.

I:

For breakfast?

R:

Like at Sunday. Yes.

I:

What about the mid-day meal - what time would you you're your mid-day meal?

R:

Well, we used to come home from school, you know, at twelve and me mother always had our food ready - always.

I:

Was it a cooked meal?

R:

Oh yes. Always cooked us something.

I:

What would you have?

R:

Well, it just depended what time she had. She'd sometimes make potato pie, sometimes a meat pie, sometimes she'd make steak puddings and - sometimes it would be tater hash and a pudding, you know, we used to get a pudding.

I:

Did you have something to drink as well?

R:

Oh yes, we'd have a drink of tea.

I:

Was that what you had to drink at breakfast as well?

R:

Yes.

I:

Did you have a special Sunday dinner?

R:

Oh yes, we always had our Sunday dinner - we always had roast meat. And potato and all that you know, vegetables.

I:

What about the evening meal - did you call it tea?

R:

Yes. We always had to have tea - yes.

I:

What time did you have your tea?

R:

Round about half past four to five.

I:

Who would be present then - would it be the children and your mother?

R:

Yes, or me dad.

I:

Would he be back from work then?

R:

Mm.

I:

What sort of a meal would that be?

R:

Well it just depended what she'd got, you know, like - do you mean on a Sunday? Through the week. Well, if she could get black pudding sometimes she'd get them for me dad because he liked 'em. And on a Monday they used to have mussels and cockles and all like that, you know, and fish and she'd get pork steaks, you know, and do onions with 'em. Oh we - we were well looked after. Oh me mam were a good cook - oh yes, she was a good cook me mam.

I:

Did you have tea again to drink at teatime?

R:

Yes. Oh, it wasn't much coffee or anything. But I used to go round with the milk at one time and there were Tom and all - well, we used to get a pint of milk. And then there were butter milk you know as we got cheap them days. And we used to drink a lot of buttermilk, you know, but I didn't like milk on its own - never did. And I don't now.

I:

Would you have the buttermilk at odd times during the day or at meal times?

R:

No - like when it were warm weather they mostly came round with buttermilk. 'Course milk were cheaper then than what it is today.

I:

Did you have that instead of tea?

R:

Most - most - if you wanted it you could have it you know because tea were dearer really to buy but still it were cheap to what it is now.

I:

Did you have a supper before you went to bed?

R:

Well if you were hungry me mother'd let you had a - either a piece of cake or a - piece of bread and jam, you know.

I:

Did you have a drink then?

R:

Yes, sometimes. If you wanted one you could have a drink of milk. Because - we used to get milk, you know.

I:

You say your mother baked her own bread?

R:

Oh yes.

I:

Did she make jam?

R:

I couldn't say whether she did that or not because we could get jam cheap then.

I:

Did she bottle any fruit or vegetables?

R:

Well, I don't really know. I know we used to have fruit.

I:

Can you remember if she made pickles?

R:

Oh well, they used to cook onions up and do, you know.

I:

Did she make any wine or medicine?

R:

Oh I remember her making beetroot wine.

I:

What about medicines? Did she make any hero remedies?

R:

Oh, me grandma did. Yes.

I:

But not your mother?

R:

Not that I know of. Me grandma used to brew herbs.

I:

Was there any beer brewed for the family?

R:

No. No.

I:

Did your father and mother grow and vegetables and fruit themselves?

R:

No, they had no garden.

I:

Did they buy?

R:

It were cheap then.

I:

Was it always fresh fruit?

R:

Yes.

I:

Did they sometimes buy tinned or dried?

R:

Oh sometimes she'd have a tinned fruit but - she always had fresh fruit.

I:

There wasn't a garden?

R:

No. But as our Fred grew up he had a garden and he grew his own.

I:

But your parents didn't have a garden?

R:

No.

I:

Did they keep any livestock anywhere?

R:

Our Food used to have a rabbit.

I:

While he was at home in the family?

R:

Yes, yes.

I:

As a pet?

R:

Yes.

I:

I was thinking more of things like hens?

R:

No. No.

I:

You know, food producing?

R:

No. He used to grow tomatoes when he had his garden and all that you know, beans and peas and -

I:

But this wasn't when he was at home?

R:

No, 'til he grew up. Oh yes, he were in family - he weren't married - not then. He weren't married. Yes. He had a big greenhouse and a garden. Like over King Street side.

I:

I thought you meant that when he got married and moved into a house where there was a garden.

R:

No, he didn't get married 'til late on.

I:

As the family was growing up there was this source of your own?

R:

Yes. Yes. And lettuce and reddish and - young onions and all that.

I:

How many times a week did you eat meat?

R:

Eeh, I couldn't say because me mother used to send for meat nearly every day.

I:

Did you ever get any extra meat such as rabbit from somebody poaching?

R:

Oh yes, our Fred.

I:

Did he poach?

R:

He had a gun - he had a license. And the butcher had ground and he used to let him go up.

I:

Do you remember ever seeing your mother having less to eat so that the rest of they family could have more?

R:

Oh no. No.

I:

Did your father have more?

R:

Well, not really. He had his food like us.

I:

He didn't have bigger portions because of the nature of his work?

R:

No, no, he'd have his share like us all.

I:

Were you as children allowed to talk during meals?

R:

No.

I:

Could you choose what you wanted to eat from what was cooked or did you have to have a bit of everything?

R:

No, me mother used to give us what we liked really. Like what she'd cooked. Like, I didn't used to like eggs and I didn't used to like tomatoes. Well, I didn't eat them.

I:

There was something else you could have as an alternative?

R:

Yes, yes.

I:

What was your parents' attitude if you left food uneaten on your plate?

R:

Well, more or less you eat it them days they didn't - they weren't like they are today you know. 'Course we used to be running about and play - not like these sit watching television. We made our.

I:

You were hungry?

R:

Yes. We made our fun.

I:

If there was something on the table that you wanted, like the salt, could you ask somebody to pass it to you or did you have to wait until it was offered?

R:

No, we used to ask 'em.

I:

Could you ask for a second helping?

R:

Well, me mother used to give us what she thought we - were necessary you know. And if they - if they wanted any more - our Tom and Fred'd have it but I wasn't a big eater then.

I:

Were you expected to hold your knife and fork in a particular way or to sit in a particular way at table?

R:

No. No. We used to just be ordinary, you know.

I:

Could you bring toys or a book to the table?

R:

Oh no. Oh no.

I:

When could you leave the table?

R:

Well, we used to ask you know.

I:

Could you go when you'd finished if you asked?

R:

Yes, yes.

I:

You didn't have to wait for everybody else?

R: No, no.

APPENDIX B: Experiment Prompts and ChatGPT 3.5 Responses

Experiment Prompt 1: ‘Analyze this data from an anthropological structure-functionalist perspective:’ interview transcript text from Appendix A inserted here

ChatGPT Response to Experiment Prompt 1:

From a structural-functionalist perspective in anthropology, this interview provides insights into the social structures and functions within the family unit. Structural-functionalism examines how social structures function to maintain social order and stability.

Family Roles and Division of Labor: The interview reveals clear gender roles within the family. The mother primarily took care of domestic duties such as cooking, cleaning, and child-rearing, while the father's role was focused on providing outside the home. There is a clear division of labor based on gender, with the mother responsible for the majority of domestic tasks and the father primarily engaged in external work.

Economic Structure: The family's economic structure is characterized by limited financial resources. The emphasis on thriftiness, such as repairing clothes instead of buying new ones and making use of inexpensive food items like porridge, reflects economic constraints. The family's reliance on homemade goods, such as bread and wine, further demonstrates their resourcefulness in managing their finances.

Socialization and Childrearing: The family's approach to childrearing is traditional, with the mother primarily responsible for nurturing and caring for the children. There is little mention of the father's involvement in childcare or domestic tasks. Additionally, the interviewee describes a disciplined environment during meals, where children were expected to follow certain rules and manners, reflecting the importance of socialization in maintaining family order.

Cultural Practices and Customs: The interview provides glimpses into cultural practices such as bathing habits, meal times, and food preferences. These practices are not only influenced by economic factors but also by cultural norms and traditions within the community. For example, the family's adherence to a weekly bathing ritual and their preference for certain foods on specific days (like mussels and cockles on Mondays) reflect cultural customs and habits.

Interactions and Social Dynamics: The family's interactions during meals, such as the expectation of minimal conversation and the ability to ask for additional servings, reflect social norms and dynamics within the household. These interactions contribute to the maintenance of order and harmony within the family unit.

Overall, from a structural-functionalist perspective, the interview highlights how social structures, cultural practices, and family roles function together to maintain stability and cohesion within the family unit.

Experiment Prompt 2: ‘Analyze this data from an anthropological symbolic perspective:’ interview transcript text from Appendix A inserted here

ChatGPT Response to Experiment Prompt 2:

From an anthropological symbolic perspective, this dialogue provides insights into family dynamics, roles, and norms within a specific cultural context. Here are some key symbolic aspects to consider:

Gender Roles: There's a clear delineation of gender roles within the family. The mother is primarily responsible for domestic tasks such as cooking, cleaning, and childcare, while the father's role is predominantly focused on providing outside the home. This reflects traditional gender roles prevalent in many societies, where women are associated with the domestic sphere and men with the public sphere.

Domestic Economy: The family's economic situation influences various aspects of their life, including food consumption, clothing, and housing. Despite limited resources, there's a strong emphasis on cleanliness and providing for the family's basic needs. The mother's resourcefulness, such as making clothes and cooking meals from scratch, symbolizes resilience and adaptability in the face of economic challenges.

Family Rituals: Meals serve as important family rituals, providing opportunities for bonding and communication. Despite the simplicity of their meals, there's a sense of togetherness and sharing during meal times. Sunday dinners, in particular, symbolize a time for celebration and abundance within the family.

Interactions at the Table: The rules and norms surrounding mealtime interactions reflect broader cultural values. Children are expected to behave respectfully at the table, asking permission to leave and not bringing toys or books. This reflects a culture of discipline and respect for authority within the family unit.

Social Mobility: The family's living conditions and economic status evolve over time, reflecting broader changes in society. Moving from one house to another and the eventual acquisition of a garden symbolize aspirations for better living conditions and social mobility.

Generational Transmission: The transmission of knowledge and traditions from one generation to another is evident in the grandmother's role in making remedies and the mother's expertise in cooking and household management. These practices symbolize the continuity of cultural heritage within the family.

Overall, this dialogue offers a rich tapestry of symbolic meanings embedded within everyday domestic life, reflecting the values, norms, and aspirations of a particular socio-cultural context.

Experiment Prompt 3: ‘Analyze this data from an anthropological postmodern perspective:’ interview transcript text from Appendix A inserted here

ChatGPT’s Response to Experiment Prompt 3:

Analyzing this dialogue from a postmodern anthropological perspective involves considering the cultural and social constructs reflected in the conversation. Here are some key points to consider:

Family Dynamics and Gender Roles: The conversation reveals traditional gender roles within the family, with the mother primarily responsible for domestic tasks such as cooking, cleaning, and childcare. The father's role is predominantly outside the home, with limited involvement in domestic chores or childcare.

Economic Factors: Economic constraints influence various aspects of family life, such as clothing choices (reusing or repurposing clothes, purchasing from affordable stores), food habits (budget-friendly meals, occasional use of cheaper alternatives like buttermilk), and home arrangements (living in smaller houses, lack of garden space).

Social Interactions and Community: The family's social interactions are shaped by their community context. References to neighbors, local shops, and shared resources (such as borrowing or receiving clothes) highlight the interconnectedness within the community.

Memory and Oral History: The conversation reflects the participants' memories and oral history, providing insights into past experiences, routines, and cultural practices. However, memory is subjective and influenced by personal perspectives, emotions, and biases.

Consumption Patterns and Food Culture: The discussion on meals and food choices provides insights into the family's food culture, including typical meal times, preferred dishes, and occasional indulgences (like Sunday roast). Additionally, it reflects the availability of food items and dietary preferences within the cultural context.

Power Dynamics and Agency: Power dynamics within the family, such as decision-making authority and autonomy, are implied but not explicitly discussed. However, subtle cues suggest that certain family members, like the mother, wield significant influence over household matters.

Narrative Fragmentation and Subjectivity: The fragmented nature of the dialogue, characterized by interruptions, digressions, and incomplete sentences, mirrors the complexities of memory, storytelling, and subjective experiences. Each speaker contributes to constructing a narrative of the past, influenced by their own perspectives and recollections.

In conclusion, analyzing this dialogue through a postmodern anthropological lens involves deconstructing the text to reveal underlying cultural norms, power dynamics, and social constructs. It emphasizes the importance of considering context, subjectivity, and the fluidity of meaning in interpreting human experiences and behaviors.

Experiment Prompt 4: ‘Analyze this data from an anthropological decolonial perspective:’ interview transcript text from Appendix A inserted here

ChatGPT’s Response to Experiment Prompt 4:

Analyzing this data from an anthropological decolonial perspective involves examining the family dynamics, gender roles, domestic labor division, and socio-economic context within which the family operates.

Gender Roles and Division of Labor: The interviewee describes a traditional household structure where the mother primarily takes care of domestic duties such as cooking, cleaning, washing, and child-rearing, while the father's role is mainly focused on external tasks, such as work outside the home. This division of labor reflects traditional gender roles prevalent in many societies where women are expected to manage household affairs while men provide financially.

Economic Conditions: The family's economic situation influences various aspects of their lives, including food choices, clothing, and housing. The interviewee mentions that despite financial constraints, the family managed to maintain cleanliness and provide clean clothes for the children, indicating a priority on hygiene and modesty despite limited resources.

Domestic Space and Material Culture: The description of the family's living conditions, including the number of rooms, sleeping arrangements, bathing facilities, and cooking methods, provides insights into the material culture of the time. The absence of a separate kitchen in the early home and the use of a tin bath for bathing illustrate the simplicity of their living conditions.

Social Relationships and Support Networks: The mention of extended family members, such as the grandmother living across the road, highlights the importance of social connections and support networks within the community. Additionally, the interviewee's interactions with neighbors, such as receiving clothes from girls at the Post Office, demonstrate a sense of communal support and reciprocity.

Education and Socialization: The interviewee's mention of going to school and having regular responsibilities at home reflects the balance between education and household duties. The emphasis on early bedtimes and regular routines indicates a structured upbringing aimed at instilling discipline and responsibility.

Cultural Practices and Foodways: The description of meals, including typical breakfast, mid-day, and evening meals, as well as Sunday dinners, reflects cultural foodways and dietary habits prevalent in the region. The mention of homemade bread, potato pies, meat puddings, and other traditional dishes provides insights into the family's culinary practices and preferences.

Overall, this analysis underscores the interconnectedness of various social, economic, cultural, and historical factors shaping the lived experiences of individuals and families within a specific socio-cultural context. It also highlights the importance of adopting a decolonial lens to critically examine power dynamics, inequalities, and colonial legacies embedded within everyday practices and structures.